On December 18, the very last day I was in Huancayo in 2011, I felt like a real Peruvian for the very first time. No, I didn’t get my Peruvian citizenship (even though I would like to be a legal Peruvian one day). This was even better: a stranger thought I was Peruvian!

Dance means a lot to Valentino, a breakdancer in Huancayo. To him, every new acrobatic move or dance step symbolizes life’s challenges. Every new achievement on the dance floor acts as a reminder that there are no limits in life.

In this video clip, Valentino shares why dance is important to him:

It takes a lot of time, effort, discipline and practice to learn a new breakdance move. You don’t always see the tangible improvements, but somehow, one day, you’re flipping and spinning on your hands, feet and head. “It’s like medicine,” Valentino says. “It relaxes me and helps me recuperate.”

As he explained this to me, I considered them lessons:

- We don’t always see that we’re growing and changing, but we have to keep chugging along and one day, we make wiser decisions and are proud of ourselves.

- When things get rough, we can call on past achievements to carry us through, and remind us of our value and strength.

Whenever I face self-doubt, I try to remind myself of the work I did in Japan. My research was on children with disabilities and it involved attending weeklong camps where we worked one-on-one with a patient using a Japanese psychorehabilitation technique.

I don’t know what changed, but something did over six more months until it came time for the last camp before returning home to Canada. This time, I didn’t have a translator, I took each therapy session as a learning experience with my trainee in which we joked and laughed together, I made friends with everyone and I eventually had a paper published on my research in an academic journal.

What is the challenge you overcame or overcome daily that reminds you that you can do anything?

In 1995, Alberto Fujimori, the former president of Peru, promoted birth control by actualizing a national family planning program as part of his agenda to decrease population growth and therefore poverty. The program involved universal access to reproductive healthcare and sex education in schools. Proponents reasoned that the program would lead to decreased maternal mortality rates and empower women, especially rural women who would gain the ability to make choices about their reproductive health.

We’re now seeing a similar phenomenon happen in the Philippines where there is currently intense debate over the Reproductive Health bills (“RH bill”) that has many of the exact same provisions as those of Fujimori’s program in 1995. This time, the Catholic Church is sure that promoting birth control, or what they refer to as “abortion-inducing drugs,” will increase rates of abortion, which is illegal there.

In countries where the Catholic Church plays an important role, should the Church also have a say in reproductive health and sex education? Should everyone in the world have equal access to birth control? Why or why not?

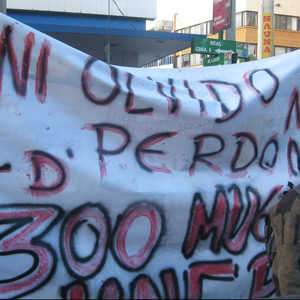

Peruvians will choose their new president in the second round of elections this Sunday. The competition is between Keiko Fujimori and Ollanta Humala who are neck to neck in the polls. Despite Ollanta’s wishy-washy proposals and his association with Hugo Chávez, he has gained a strong following with many of his supporters hardly voting for him than voting against Keiko.

Many people remember Alberto Fujimori for embezzling tons of money from the government and for killing off their families during the harsh stance he took against the terrorists, which often involved innocent people. Fujimori apologists argue that these undertakings were primarily headed by Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori’s chief advisor.

Below is a short clip of Keiko’s most recent visit to Huancayo last week during her presidential campaign. As she comes down the stairs amongst shouts of “Keiko for President!” you’ll hear a man shout: “China Rata!” calling her a rat as an insult.

Should Keiko be blamed for her father’s wrongs? Are you just like your parents? Can we ever really dissociate ourselves from our family? Will their errors always reflect on us and our errors on them?

Yesterday, Nestle Milo hosted their annual five-kilometer race through the city — the Milothon. Out of the near 10,000 youth that participated in the event, the winner, in my eyes, was a 17-year-old in crutches who finished the race strong.

What instantly captivated me about Christian was his cheerfulness and warmth, even as he told me about the naysayers along the route. He kept on keeping on despite those who pitied and ridiculed him along the path. They told him that this race wasn’t for people like him. Little did they know that the Milothon hasn’t been his only event. He also finished the Andes Marathon — yes, the full 26.2 miles — even though it took him double the time that it takes a typical runner.

Nevertheless, you don’t see Christian asking for pity. He says that he wants to study medicine and I think Huancayo needs more doctors who have his strength, compassion and humility.

Feel Christian’s warmth yourself in this short message he wanted to share with all of you:

How have you shown enthusiasm and perseverance against a recent obstacle in your life?

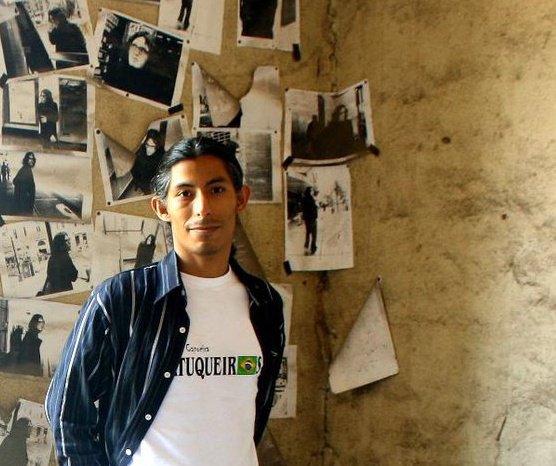

“El arte nace del mar de la inconformidad.” – Elio Osejo [Art is born from the sea of nonconformity.]

Elio Osejo is recognized as a famous name from “Juliana,” one of the most well-known Peruvian films of all time, but you wouldn’t know it from the humble and quiet lifestyle he now lives off the beaten path in the middle of the Central Andes. In his role in “Juliana,” the other street kids dubbed him with the nickname “loco” (crazy). It wasn’t because he played a crazy kid, but because he was different from the gang; he was an observer, read the newspaper and spoke wise words for someone so young: “Más y más inflación. Los precios se inflan y los platos se desinflan.” [More and more inflation. The prices inflate and the dishes of food deflate.] True to his character, the Peruvian public called the real life Elio, “loco,” because he never took on another role in his native country despite promises of fame and fortune. He explains that he wants to be constructive and not destructive in his art, but all the lucrative roles they pitched him were of negativity, murder and defeatist stereotypes.

To this day, he remains a nonconformist. As would be expected by society, people try to put him into labeled boxes:

- For his poetic background

- For his tendency to initiate and provoke conversation and discussion

- For his ponytailed long hair

- For his eccentricity

Some thoughts on the subject from Elio:

| Adáptate o Muere | Adapt or Die |

| “Adáptate o muere” me decía mi padre | “Adapt or die” my father told me |

| quien se adaptò un dia a su nueva familia | who adapted one day to his new family |

| y desde entonces no supimos màs de èl | and we never heard more of him from then on |

| “Adáptate o muere” me decía mi madre | “Adapt or die” my mother told me |

| que arrastraba su estigma de leona solitaria | who dragged around her stigma of a solitary lioness |

| y conversaba con sus plantas para no sentir que yo | and conversed with her plants to not feel that I |

| tambien me iba alejando poco a poco de la casa | too was slowly drifting away from home |

| “Adáptate o muere” me decía el sargento sin saber | “Adapt or die” the sergeant told me, not knowing |

| que más tarde descubriría la paz de las mujeres y que | that soon I would discover the peace of women and that |

| mi eterna batalla sería siempre en contra del aburrimiento | my eternal battle would always be against boredom |

| “Adáptate o muere” me decían mis profes | “Adapt or die” my professors told me |

| “Adáptate o muere” me decían mis jefes | “Adapt or die” my bosses told me |

| Miro hacia atrás y escribo satisfecho: | I look back and write satisfied: |

| “La vida nunca dejará de ser maravillosa | “Life will never stop being marvelous |

| hasta para un desadaptado como yo” | even for someone who hasn’t adapted like me” |

Elio doesn’t fit cleanly into any of the boxes people make for him, if at all, but he does dabble in all communities because he believes that art is about sharing and depends on a deep understanding of life by living it thoroughly. With an attitude of openness, connecting with others provides more than information and inspiration; it provides new artistic possibilities. As Elio reminds me through the wisdom of Zen, we need to continually empty our metaphorical cup and refill it with freshness.

These days, you will find Elio immersed in his latest two passions: poetry and capoeira. Capoeira embodies his philosophy of art and life — it’s not about a fight, but a jogo (game) as the Brazilians say. He teaches his young capoeira students to smile because the goal of capoeira is not about winning. Likewise, writing is not about stardom or money and life is not about achieving happiness. Instead, you live your art as a form of “elevated expression” and live happiness through shared moments, the little things.

What boxes do people try to stuff you into?

—

A big thanks to Elio Osejo for his time and for the interview.

When I look at my schedule and think of all the occasions I attend, I feel a serious lack of special, formal, and large-scale events in Canada other than weddings. (Speaking of which, does that mean people who decide not to marry are just not special enough?) Here in Peru, above and beyond the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church, many young ladies commemorate their coming-of-age when they turn 15 years old at a quinceañera. It’s a major affair almost at par with her wedding day in terms of unreserved attention to the celebrant, recognition from family and friends, and nostalgic moments.

Saturday’s quinceañera was as grand as I imagined them to be. The hall was decorated like a dream – the flowery adornments, entranceway, tables, and chairs were all decked out in the night’s theme colours of cream and purple. We arrive at the location at 10pm. The invitation says to arrive at 9:30pm, but nothing starts until midnight. (Have I ever mentioned that Peruvians are notorious for arriving late? The two-and-a-half hour timeframe is to make sure that everyone arrives on time). So, what do we do for two hours? Eat and drink. Waiters continuously pass by each table with different hors d’oeuvres. As for drinks, each guest has four different sizes of glasses for different types of liquor – pisco sour to start off the night, champagne for the toast, wine for the dinner, and then beer for the dancing. There is no water glass.

During this time, the special lady is spending special moments with her special chosen partner for the night – typically a boyfriend if she has one or at least someone she has a crush on. There’s also a photo session that almost always includes photos on a decorated swing to commemorate her childhood. At midnight, they finally make their way over to the hall.

Traditionally, the star of the show is in a white gown and tiara and at midnight, slowly walks down spiral stairs for all to see. This star is too cool for that. She arrives on the back of a motorbike in a deep purple dress and the night begins. She takes her father’s arm and he walks her down the aisle where 15 of her friends, including the crush, line the way armed with a candle and a rose each. The father leads her to each friend, where she blows out the candle signifying each year of her life that has passed and receives a rose. Afterwards, the father and godfather of the night give teary speeches about how much she has grown and matured, and then the mother gives a toast for her daughter’s future. We reminisce with the family as we watch a slideshow presentation of her life, are treated to a waltz-like choreography by the friends, and enjoy a presentation from the star herself with two masked dancers to accompany her. Then, the rest of the night is all about dancing – a private area is darkened and set up like a club for the young people while the rest of the hall is taken up by the older people, and everyone dances away until dawn.

The first phase of the project has finally come to an end. We have officially conducted sixty parent questionnaires in sixty homes to assess the general development of sixty babies. As we take our first peeks at the data we’ve collected and as we clarify and refine the approach for the second stage of the project (much to the surprise, confusion, and sometimes frustration of Maria and I), I have had more than a couple moments of the “What am I doing here?” sentiment.

There is first the “What am I doing here? I’m not right for this job. You have the wrong impression of me. Everyone has been introducing me as a ‘specialist,’ but that doesn’t mean my textbook knowledge is more valuable than your empirical experience. How can I give you advice on parenting? I’m not even a mother yet. I don’t think that I know enough to teach you anything new or to answer all of your questions properly. In fact, maybe I don’t know what I’m doing at all.”

Then there’s the “What am I doing here? I’m now realizing how massive this project is. How can we interpret the data properly? There is so much more that I need to know. Why do the mothers here behave the way they do? How much of this is attributable to culture? How much of the culture do I have yet to understand? How can I possibly contribute to this project if I don’t understand the people I’m studying? I should have locked myself in my room, reading about Peru, when I had the chance to in Nova Scotia. I should have at least travelled to Latin America before. I should have…”

Of the six different areas of development we evaluated, the most staggering outcome of the infant assessments was a clear deficit in infants’ social-emotional development. This area of development refers to their ability to manage or regulate their emotional and social behaviour in a way that society considers appropriate and acceptable. And this is where it gets tricky – what is “appropriate” and “acceptable” in this context and who decides?

Some examples of questions I had a difficult time consolidating:

- One of the questions on the social-emotional questionnaire asks something along the lines of: “Can your baby calm him/herself within a certain period of time if you leave his/her side?” We found that a decent chunk of mothers responded no to this question, but we also noticed that many mothers didn’t seem to be worried that their baby could not “regulate his/her emotions” as we would say in child-development-speak. “No, of course my baby can’t be without me,” was a classic answer. At the same time, over 90% of the mothers were amas de casa (housewives) who spend almost 100% of their time with their babies. Is it so surprising that their babies are not accustomed to being alone?

- Another question asks if the baby ever puts a banana to his ear, pretending it’s a telephone, or puts some other object on top of his head, pretending it’s a hat. I clearly remember one mother’s answer – in a tone suggesting that she was a little offended – which, to me, explains a common attitude towards pretending/imagination here, “If my baby knows it’s a banana, why would he use it as a telephone?” This strikes my “chicken and egg” curiosity – is this attitude a result of the living situation or does the lack of pretend play (which links to creativity) speak to the way people live here?

- During some of the interviews, Maria and I would sometimes notice violence being encouraged. “Go hit the pig to scare it out of the house.” “Throw something at the dog so it’ll stop eating out of the garden.” This had implications for one of the social-emotional questions that asks if the infant or child is ever violent towards other children or animals. But being commanded to be violent towards animals in this way doesn’t necessarily imply an inherent violent nature, neither at this age nor in the future.

The question, then, is whether we can make solid conclusions about the infants’ social-emotional development if it may be considered acceptable and appropriate, at least in some of the towns we visited, for babies to be unable to regulate their emotions without their mothers, for babies to not engage in pretend play, and for babies to show occasional violence towards animals.

Part of me feels a little disillusioned – I knew I couldn’t come here and be a hero, but I’m now recognizing a small part of me that wanted to save the world. There is the temptation to say, “This is how it works where I come from. You’re doing it all wrong. You should do it this way,” and to be harshly honest, I have met my share of development specialists who harbour this attitude. For this reason alone, I’ve found that it’s so important for me to say “I don’t know” and to not be afraid of admitting it. I’m not sure what’s best for you. How can I tell you that the North American theories of parenting are best, let alone that they apply in this context? I can’t make the conclusion that you don’t love your child because you don’t spend a lot of time with him/her – your priorities are drastically different and I respect that needing to survive can be more important than finding time to play with your child.

So, I have come full circle back to the approach I knew I should have had from the beginning – ultimately, this is about sharing. It’s about taking advantage of what little time we do have here to exchange preoccupations, thoughts, and ideas. I learn from you as much as you learn from me. I dispel some of your unawareness of the importance of play, for example, and you teach me the importance of simplicity and working hard. Your knowledge is just as valuable as mine if not more valuable. I am honoured to absorb your wisdom.

This week, Maria and I are wrapping up phase one of our infant stimulation project in Peru – the individual home visits and infant assessments. We’ve visited five different towns in and around Huancayo, each with a very different feel and personality. Some random thoughts and experiences to summarize it all…

- We gave a workshop in Paucar (one of the more rural towns) teaching moms how important it was to sing songs to and with their babies. I gave my first introductory lesson on the importance of singing to your children (speaking completely in Spanish – okay, it only lasted 2 minutes), then sang song after song, hitting the dry grass like martillos (hammers), pretending to be gusalinos (little worms), and acting out Dinky Dinky spider (no joke, that’s Itsy Bitsy’s name here!) Even with my sore throat, I belted out tune after screechy tune, not fully believing that there I was, leading this group of moms and their babies, singing in Spanish.

- It was an adventure in every town, locating the mothers as most of the houses are S/N (sin numero = without number). Sara and I had a particularly interesting morning walking back and forth across chacras (farms) because different people we ran into told us that the other street was Avenida Andre Avelino Caceres. As there usually aren’t any street signs in more rural areas of town, street names are often painted on the sides of houses – and even then, we never found the street we were looking for. So we piled into the colectivo (like a taxi, but they let anyone on), thankful that we weren’t one of the five packed into the trunk, and headed on to the next home.

- The moms in Chupaca had a bit more money and almost every family, good hosts as they were, either fed us or at least served us coke. I have never had so much gaseosa (pop) in my life and I don’t even particularly like soda. On top of all this, I already have a bladder problem and try to make sure not to drink too much when we’re going out to the towns all day. Little good that did.

- Animals are a general theme of the houses we visited. There always seem to be dogs, hens, pigs, and cows running around, participating in the assessment sessions. Often, one can find guinea pig pens with guinea pigs of all kinds of colours, shapes, and sizes. And can someone tell me if the gallinas (hens) lay eggs wherever they want to since they’re running around all the time? =)

- The oldest babies we see are 30 months old (2 years, 6 months), and moms are still breastfeeding at this age.

- I was surprised to see some babies with natural stark blonde hair – super adorable. Sara later mentioned that the hair colour could possibly be from malnutrition. Didn’t even think of that.

- In Molinos, the furthest town, almost two hours away from Huancayo, we got caught in a mini storm. We could hear the thunder as if it boomed right beside our ears. The rain came suddenly and in spurts, sometimes sprinkling then other times intense with huge droplets almost like hail. Sara and I conducted an interview standing under a tiny awning with the mother, trying not to get our papers soaked. With another family, we huddled with them under a tarp in the middle of their farm, sitting on wood chips, getting bitten by fleas and tiny spiders, watching the father carve Jesus’ face out of sections of tree trunk.

- For those of you that are wondering, I am almost always wearing a toque now to hide my silly haircut. =) It works out well for the weather – protects my face from the UV rays, but doubles as a head warmer when it randomly gets cold out. And no, I’m not the only one here who wears a toque under the blazing hot sun!

Copyright © 2024 Samantha Bangayan | Sitemap | Disclosure Policy | Comment & Privacy Policy

All articles and photos in this blog are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.